It is an accepted fact that a bullet or a bullet fragment struck the concrete curb on the north side of Main Street near the Triple Overpass. A nearby onlooker, James Tague (see photos above), was struck on the cheek by the ricocheting concrete or a minute shred of the fragmenting bullet.

Since photographs of Tague’s wounded cheek and the damaged curb were published immediately after the assassination, the Warren Commission had no choice but to account for the errant shot. Because the physical evidence (the three spent hulls found on the sixth floor) and the duration of time between the first and last shots would not allow lone assassin Oswald a fourth shot, it demanded that all the wounds to the President and Governor Connally were caused by just two bullets.

Enter the Single Bullet Theory. Arlen Specter, a junior Council on the Commission staff, reasoned that since Governor Connally was seated directly in front of the President, it was extremely likely that one bullet could have hit Kennedy from behind, exited through the wound in his throat, and continued on to inflict the Governor’s wounds.

It almost made sense. Fragments of one bullet had been found in the limousine, underneath the front seat. This was undoubtedly the bullet that struck the President in the head. Another intact bullet was discovered on a stretcher in Parkland Hospital. This bullet was designated the cause of all of all the other wounds to the President and Governor Connally. The third bullet missed the vehicle altogether, and struck the curb by the Triple Overpass wounding James Tague.

Certainly the numbers added up. Three shells were found in the Depository. Two hit their mark, and were recovered. One missed, left its mark on the curb, and was never found. A majority of witnesses reported hearing three shots.

However, the case against Oswald as lone gunman disintegrates upon closer scrutiny. Zapruder clearly demonstrates that Kennedy and Connally were not struck by the same bullet. This is supported by Governor Connally’s account of the assassination as well as the bullet holes in the President’s jacket and shirt.

Moreover, it is highly unlikely that Oswald fired the shot that damaged the curb by James Tague. The Warren Commission reported that the mark on the curb was "spectrographically determined to be essentially lead with a trace of antimony." Despite the impreciseness of words like essentially and trace, it is clear that the mark was not made by a copper-jacketed bullet like the ones allegedly used by Oswald. The Commission points out that it could have been made by a fragment of the bullet’s core, which is lead, but considering that the curb was approximately 260 feet from the limousine at the moment of the fatal head shot, it is hard to imagine a fragment striking the curb with that much force. And since the Commission contends that the bullet entered the back of the President’s head and blew out the right side of his skull, how could a fragment deflect to the left without damaging the left side of his head as well?

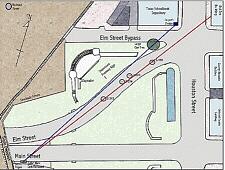

And if Oswald did fire that shot, where was he aiming? The trajectory from the sniper’s window to the damaged curb would be well right of his target, fifteen to twenty feet off-line. Oswald would have had to get off a shot after Z-400 for it to have been in line with the mark in the curb. (Click here for a larger version of this map).

In Case Closed, Gerald Posner theorizes that Oswald’s first shot (he places it about Zapruder Frame 160) struck the Oak tree, which caused the jacket to separate from the core of the bullet. The copper jacket was deflected, struck the pavement behind the limousine, where is was seen making sparks by Virgie Rachley. The lead core continued on a straight course, striking the curb near James Tague. Let’s call this one Magic Bullet II. Did any of the many witnesses standing beneath or near that tree see a branch falling, or report the sound of a bullet hitting the tree? No. Was there any physical evidence of such a phenomenon happening? No. No copper jacket, or no lead core was found. This explanation is a desperate attempt to explain two documented stray bullets with just one missed shot.

If Mr. Posner’s assertion is correct, why did Oswald pass up a clear shot at the President on Houston Street, only to shoot blindly through a large oak tree moments later? And the question must be asked again and again and again, where was Oswald aiming? Mr. Posner correctly points out that the tree is in direct line with the mark on the curb and the sixth floor window, but fails to mention how far right of the mark that shot would have been. Nor does he bother to explain how someone firing from the sixth floor, at a target below him, could overshoot the limousine by so much.

Because the motorcade was travelling down an incline during the time of the shooting, it’s reasonable to conclude that the shooter failed to hit his target because he did not properly compensate for the angle of declination. Most probably, the Tague shot just narrowly missed striking the top of the President’s head, barely clearing the limousine. Since a missed high to low shot (such as from the sixth floor Depository window) would have to pass several feet over the intended mark, it seems likely that the shooter had to be positioned on the same plane or slightly above his target.

The likely origin of the missed Tague shot would be one of

the lower floors of the Dal-Tex building. Looking at the diagram

of Dealey Plaza printed above, the red line represents a shot

fired from the Dal-Tex building to the damaged curb. It traverses

the limousine throughout the entire shooting sequence! Any shot

fired from the Dal-Tex Building at the motorcade would be directly

on line with the damaged curb!

In fact, the Dal-Tex Building is the logical choice for an assassin

firing from behind. Unlike the sixth floor Depository window,

there are no obstructions like the oak tree that supposedly blocked

Oswald’s view. And as the limousine moved down Elm Street,

the angle would remain constant, making it easier for the shooter

to track his target.

Assassination researcher Robert Groden, who served as a photographic consultant for the House Select Committee for Assassinations, believes that a photograph taken by James Altgens might reveal one of the conspirators in the Dal-Tex Building. The dark-complected man, who has never been identified, leans suspiciously out of a broom closet window just seconds after the President and Governor Connally were struck from behind. As mentioned above, this location would be on line with the Tague shot and a perfect vantage point for an assassin.

Several people in Dealey Plaza (including Phillip Willis and his family) witnessed the arrest of a young man wearing a black leather jacket and black gloves. He was ushered out of the Dal-Tex building by two uniformed policemen, who put him in a police car and drove away from the crime scene as the crowd cursed and jeered him. There is no official record of this arrest.

Approximately fifteen minutes after the assassination, the

elevator operator in the Dal-Tex Building noticed an unknown man

inside the building. Feeling that the man didn’t belong in

the building, the elevator operator sought out a policeman, who

detained the suspicious man, bringing him to the sheriff’s

office for questioning. They held him for nearly three hours.

He told police that his name was Jim Braden, and that he was in

Dallas on oil business. He showed them identification, and explained

that he had entered the building in hopes of finding a telephone

to call his mother. Braden further asserted that he entered the

building only after the assassination occurred, although eyewitnesses

placed him in the building at the time the shots were actually

fired. Eventually, the police accepted his explanation and released

him. As suspicious as the Jim Braden incident might seem on the

surface, the underlying facts are even more incriminating. Jim

Braden was actually Eugene Hale Brading, an ex-con from Southern

California with reputed underworld ties. On September 10, just

two months before the assassination, Brading had his name legally

changed to Braden. Had Dallas police known his actual name, they

would have learned that he was a parolee with thirty-five arrests

on his record.

Brading had told his parole officer that he was going to Dallas

on oil business, and his parole records indicated that he planned

to meet with Lamar Hunt. Although he later denied meeting with

Hunt, a witness (Hunt chief of security Paul Rothermal) placed

Brading and three friends at the offices of Lamar Hunt on the

afternoon before the assassination. Brading’s presence at

Hunt’s office was also confirmed in an FBI report. Coincidentally,

Jack Ruby accompanied a young woman to the Hunt’s office

that same afternoon. And on the twenty-first, Brading checked

into the Cabana Hotel in Dallas, where Jack Ruby just happened

to visit sometime around midnight that evening.

Brading’s "oil business" brought him in close proximity to several figures long suspected in the assassination of John Kennedy. During the months preceding the assassination, Brading kept an office in the Pete Marquette Building in New Orleans. Also occupying an office in that building, on the same floor and just down the hall, was G. Wray Gill, a lawyer for New Orleans crime boss Carlos Marcello. One of Gill’s detectives was David Ferrie, who had been in and out of Gill’s office many times during the time Brading kept an office there. Ferrie later became the focus of New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison’s investigation into the Kennedy assassination. And Marcello, who had unceremoniously been deported to the jungles of Guatemala by Attorney General Robert Kennedy, had been on record making threats against the Kennedy brothers.

When Bobby Kennedy’s name came up at a September 1962 meeting, Marcello became enraged. "Don’t worry about that little Bobby son-of-a-bitch," Marcello reportedly said. "He’s going to be taken care of. Livarsi na petra di la scarpa." Translated, that means, "Take the stone out of my shoe." Then Marcello, comparing Bobby to the tail of a dog and the President as the head, remarked that if you cut off the dog’s tail, he will still bite you. But if you remove the head, he reasoned, the whole dog will die.

On the evening of June 4, 1968, Brading checked in to the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles, more than a hundred miles from his home. Just a few minutes away at the Ambassador Hotel, Robert Kennedy was murdered in the hotel pantry after winning the California primary. Upon learning of Brading’s close proximity to the Ambassador Hotel that evening, the Los Angeles Police Department was concerned enough to question Brading about his possible role in both assassinations.

Jerry McLeer

Return to Home Page

Return to Top of Page

Go to Killer on the Knoll

Who was Percy Foreman?

Did Greer Shoot JFK?

Is the Rifle in the Backyard Photo the same

one found in the Depository?