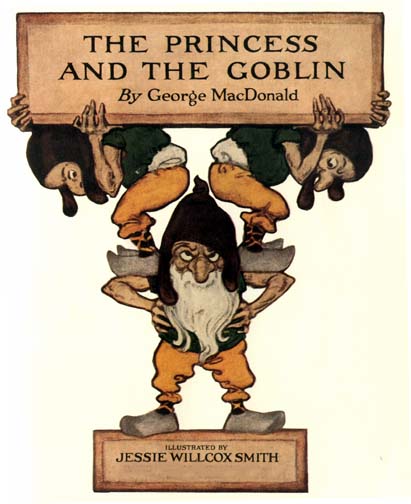

The Princess and the Goblin

by George MacDonald

Illustrated by Jessie Willcox Smith

and Arthur Hughes

The Princess & The Goblin

CHAPTER 24

Irene Behaves Like a Princess

When the princess awoke from the sweetest of sleeps, she found her nurse bending over her, the housekeeper looking over the nurse's shoulder, and the laundry- maid looking over the housekeeper's. The room was full of women-servants; and the gentlemen-at-arms, with a long column of servants behind them, were peeping, or trying to peep in at the door of the nursery.

'Are those horrid creatures gone?' asked the princess, remembering first what had terrified her in the morning.

'You naughty, naughty little princess!' cried Lootie.

Her face was very pale, with red streaks in it, and she looked as if she were going to shake her; but Irene said nothing - only waited to hear what should come next.

'How could you get under the clothes like that, and make us all fancy you were lost! And keep it up all day too! You are the most obstinate child! It's anything but fun to us, I can tell you!'

It was the only way the nurse could account for her disappearance.

'I didn't do that, Lootie,' said Irene, very quietly.

'Don't tell stories!' cried her nurse quite rudely.

'I shall tell you nothing at all,' said Irene.

'That's just as bad,' said the nurse.

'Just as bad to say nothing at all as to tell stories?' exclaimed the princess. 'I will ask my papa about that. He won't say so. And I don't think he will like you to say so.'

'Tell me directly what you mean by it!' screamed the nurse, half wild with anger at the princess and fright at the possible consequences to herself.

'When I tell you the truth, Lootie,' said the princess, who somehow did not feel at all angry, 'you say to me "Don't tell stories": it seems I must tell stories before you will believe me.'

'You are very rude, princess,' said the nurse.

'You are so rude, Lootie, that I will not speak to you again till you are sorry. Why should I, when I know you will not believe me?' returned the princess. For she did know perfectly well that if she were to tell Lootie what she had been about, the more she went on to tell her, the less would she believe her.

'You are the most provoking child!' cried her nurse. 'You deserve to be well punished for your wicked behaviour.'

'Please, Mrs Housekeeper,' said the princess, 'will you take me to your room, and keep me till my king-papa comes? I will ask him to come as soon as he can.'

Every one stared at these words. Up to this moment they had all regarded her as little more than a baby.

But the housekeeper was afraid of the nurse, and sought to patch matters up, saying:

'I am sure, princess, nursie did not mean to be rude to you.'

'I do not think my papa would wish me to have a nurse who spoke to me as Lootie does. If she thinks I tell lies, she had better either say so to my papa, or go away. Sir Walter, will you take charge of me?'

'With the greatest of pleasure, princess,' answered the captain of the gentlemen-at-arms, walking with his great stride into the room.

The crowd of servants made eager way for him, and he bowed low before the little princess's bed. 'I shall send my servant at once, on the fastest horse in the stable, to tell your king-papa that Your Royal Highness desires his presence. When you have chosen one of these under-servants to wait upon you, I shall order the room to be cleared.'

'Thank you very much, Sir Walter,' said the princess, and her eye glanced towards a rosy-cheeked girl who had lately come to the house as a scullery-maid.

But when Lootie saw the eyes of her dear princess going in search of another instead of her, she fell upon her knees by the bedside, and burst into a great cry of distress.

'I think, Sir Walter,' said the princess, 'I will keep Lootie. But I put myself under your care; and you need not trouble my king-papa until I speak to you again. Will you all please to go away? I am quite safe and well, and I did not hide myself for the sake either of amusing myself, or of troubling my people. Lootie, will you please to dress me.'

CHAPTER 25

Curdie Comes to Grief

Everything was for some time quiet above ground. The king was still away in a distant part of his dominions. The men-at-arms kept watching about the house. They had been considerably astonished by finding at the foot of the rock in the garden the hideous body of the goblin creature killed by Curdie; but they came to the conclusion that it had been slain in the mines, and had crept out there to die; and except an occasional glimpse of a live one they saw nothing to cause alarm. Curdie kept watching in the mountain, and the goblins kept burrowing deeper into the earth. As long as they went deeper there was, Curdie judged, no immediate danger.

To Irene the summer was as full of pleasure as ever, and for a long time, although she often thought of her grandmother during the day, and often dreamed about her at night, she did not see her. The kids and the flowers were as much her delight as ever, and she made as much friendship with the miners' children she met on the mountain as Lootie would permit; but Lootie had very foolish notions concerning the dignity of a princess, not understanding that the truest princess is just the one who loves all her brothers and sisters best, and who is most able to do them good by being humble towards them. At the same time she was considerably altered for the better in her behaviour to the princess. She could not help seeing that she was no longer a mere child, but wiser than her age would account for. She kept foolishly whispering to the servants, however - sometimes that the princess was not right in her mind, sometimes that she was too good to live, and other nonsense of the same sort.

All this time Curdie had to be sorry, without a chance of confessing, that he had behaved so unkindly to the princess. This perhaps made him the more diligent in his endeavours to serve her. His mother and he often talked on the subject, and she comforted him, and told him she was sure he would some day have the opportunity he so much desired. Here I should like to remark, for the sake of princes and princesses in general, that it is a low and contemptible thing to refuse to confess a fault, or even an error. If a true princess has done wrong, she is always uneasy until she has had an opportunity of throwing the wrongness away from her by saying: 'I did it; and I wish I had not; and I am sorry for having done it.' So you see there is some ground for supposing that Curdie was not a miner only, but a prince as well. Many such instances have been known in the world's history.

At length, however, he began to see signs of a change in the proceedings of the goblin excavators: they were going no deeper, but had commenced running on a level; and he watched them, therefore, more closely than ever. All at once, one night, coming to a slope of very hard rock, they began to ascend along the inclined plane of its surface. Having reached its top, they went again on a level for a night or two, after which they began to ascend once more, and kept on at a pretty steep angle. At length Curdie judged it time to transfer his observation to another quarter, and the next night he did not go to the mine at all; but, leaving his pickaxe and clue at home, and taking only his usual lumps of bread and pease pudding, went down the mountain to the king's house. He climbed over the wall, and remained in the garden the whole night, creeping on hands and knees from one spot to the other, and lying at full length with his ear to the ground, listening. But he heard nothing except the tread of the men-at-arms as they marched about, whose observation, as the night was cloudy and there was no moon, he had little difficulty in avoiding. For several following nights he continued to haunt the garden and listen, but with no success.

At length, early one evening, whether it was that he had got careless of his own safety, or that the growing moon had become strong enough to expose him, his watching came to a sudden end. He was creeping from behind the rock where the stream ran out, for he had been listening all round it in the hope it might convey to his ear some indication of the whereabouts of the goblin miners, when just as he came into the moonlight on the lawn, a whizz in his ear and a blow upon his leg startled him. He instantly squatted in the hope of eluding further notice. But when he heard the sound of running feet, he jumped up to take the chance of escape by flight. He fell, however, with a keen shoot of pain, for the bolt of a crossbow had wounded his leg, and the blood was now streaming from it. He was instantly laid Hold of by two or three of the men-at-arms. It was useless to struggle, and he submitted in silence.

'It's a boy!' cried several of them together, in a tone of amazement. 'I thought it was one of those demons. What are you about here?'

'Going to have a little rough usage, apparently,' said Curdie, laughing, as the men shook him.

'Impertinence will do you no good. You have no business here in the king's grounds, and if you don't give a true account of yourself, you shall fare as a thief.'

'Why, what else could he be?' said one.

'He might have been after a lost kid, you know,' suggested another.

'I see no good in trying to excuse him. He has no business here, anyhow.'

'Let me go away, then, if you please,' said Curdie.

'But we don't please - not except you give a good account of yourself.'

'I don't feel quite sure whether I can trust you,' said Curdie.

'We are the king's own men-at-arms,' said the captain courteously, for he was taken with Curdie's appearance and courage.

'Well, I will tell you all about it - if you will promise to listen to me and not do anything rash.'

'I call that cool!' said one of the party, laughing. 'He will tell us what mischief he was about, if we promise to do as pleases him.'

'I was about no mischief,' said Curdie. -

But ere he could say more he turned faint, and fell senseless on the grass. Then first they discovered that the bolt they had shot, taking him for one of the goblin creatures, had wounded him.

They carried him into the house and laid him down in the hall. The report spread that they had caught a robber, and the servants crowded in to see the villain. Amongst the rest came the nurse. The moment she saw him she exclaimed with indignation:

'I declare it's the same young rascal of a miner that was rude to me and the princess on the mountain. He actually wanted to kiss the princess. I took good care of that - the wretch! And he was prowling about, was he? Just like his impudence!' The princess being fast asleep, she could misrepresent at her pleasure.

When he heard this, the captain, although he had considerable doubt of its truth, resolved to keep Curdie a prisoner until they could search into the affair. So, after they had brought him round a little, and attended to his wound, which was rather a bad one, they laid him, still exhausted from the loss of blood, upon a mattress in a disused room - one of those already so often mentioned - and locked the door, and left him. He passed a troubled night, and in the morning they found him talking wildly. In the evening he came to himself, but felt very weak, and his leg was exceedingly painful. Wondering where he was, and seeing one of the men-at-arms in the room, he began to question him and soon recalled the events of the preceding night. As he was himself unable to watch any more, he told the soldier all he knew about the goblins, and begged him to tell his companions, and stir them up to watch with tenfold vigilance; but whether it was that he did not talk quite coherently, or that the whole thing appeared incredible, certainly the man concluded that Curdie was only raving still, and tried to coax him into holding his tongue. This, of course, annoyed Curdie dreadfully, who now felt in his turn what it was not to be believed, and the consequence was that his fever returned, and by the time when, at his persistent entreaties, the captain was called, there could be no doubt that he was raving. They did for him what they could, and promised everything he wanted, but with no intention of fulfilment. At last he went to sleep, and when at length his sleep grew profound and peaceful, they left him, locked the door again, and withdrew, intending to revisit him early in the morning.

CHAPTER 26

The Goblin-Miners

That same night several of the servants were having a chat together before going to bed.

'What can that noise be?' said one of the housemaids, who had been listening for a moment or two.

'I've heard it the last two nights,' said the cook. 'If there were any about the place, I should have taken it for rats, but my Tom keeps them far enough.'

'I've heard, though,' said the scullery-maid, 'that rats move about in great companies sometimes. There may be an army of them invading us. I've heard the noises yesterday and today too.'

'It'll be grand fun, then, for my Tom and Mrs Housekeeper's Bob,' said the cook. 'They'll be friends for once in their lives, and fight on the same side. I'll engage Tom and Bob together will put to flight any number of rats.'

'It seems to me,' said the nurse, 'that the noises are much too loud for that. I have heard them all day, and my princess has asked me several times what they could be. Sometimes they sound like distant thunder, and sometimes like the noises you hear in the mountain from those horrid miners underneath.'

'I shouldn't wonder,' said the cook, 'if it was the miners after all. They may have come on some hole in the mountain through which the noises reach to us. They are always boring and blasting and breaking, you know.'

As he spoke, there came a great rolling rumble beneath them, and the house quivered. They all started up in affright, and rushing to the hall found the gentlemen-at-arms in consternation also. They had sent to wake their captain, who said from their description that it must have been an earthquake, an occurrence which, although very rare in that country, had taken place almost within the century; and then went to bed again, strange to say, and fell -fast asleep without once thinking of Curdie, or associating the noises they had heard with what he had told them. He had not believed Curdie. If he had, he would at once have thought of what he had said, and would have taken precautions. As they heard nothing more, they concluded that Sir Walter was right, and that the danger was over for perhaps another hundred years. The fact, as discovered afterwards, was that the goblins had, in working up a second sloping face of stone, arrived at a huge block which lay under the cellars of the house, within the line of the foundations.

It was so round that when they succeeded, after hard work, in dislodging it without blasting, it rolled thundering down the slope with a bounding, jarring roll, which shook the foundations of the house. The goblins were themselves dismayed at the noise, for they knew, by careful spying and measuring, that they must now be very near, if not under the king's house, and they feared giving an alarm. They, therefore, remained quiet for a while, and when they began to work again, they no doubt thought themselves very fortunate in coming upon a vein of sand which filled a winding fissure in the rock on which the house was built. By scooping this away they came out in the king's wine cellar. No sooner did they find where they were, than they scurried back again, like rats into their holes, and runn